Results

2,284 Results

Loading more Results ...

Loading more Results ...

Wine regions in Champagne 3 growing regions

Description to Champagne

Sparkling wine from France is probably the most famous alcoholic beverage and epitomises joie de vivre and luxury. As early as 1531, a sparkling wine was documented in south-west France, namely the Blanquette de Limoux from the village of Limoux. But in Champagne, champagne was by no means synonymous with this type of wine in the first half of the 17th century. A common phenomenon in this region was that fermentation was interrupted in autumn due to the cool weather and the wines were bottled anyway. When the weather warmed up in spring, the residual sugar triggered an unplanned or unwanted second fermentation in the bottle. Initially, there was no intention behind it, it just happened by chance.

The "invention" of champagne

The deliberate production of champagne, i.e. the "invention" of the sparkling beverage, is often wrongly attributed to the Benedictine monk Dom Pierre Pérignon (1638-1715). A statuette of him stands in the headquarters of the largest champagne house Moët et Chandon in Épernay, which also produces a brand named after him. However, it is an indisputable fact that he brought the skilful blending of vintages, grape varieties and sites to perfection. But not only did he not aim for a second fermentation in the bottle, he also tried to prevent the undesirable process through various measures. One of these was to use more red wine grapes.

The satirist Marquis de Saint-Évremond (1610-1703), who went into exile in London due to disputes with the Prime Minister of Louis XIV (1638-1715), made an important contribution to its popularity. From 1661, he introduced white wines from Champagne in barrels. Due to the warm spring weather, a second fermentation was often started in the barrel. The lively, sparkling wines were bottled on arrival and quickly became a popular drink, especially in aristocratic circles. These were the primitive forerunners of champagne, twenty years before Dom Pierre Pérignon began to work on it. A "sparkling champagne" was first mentioned in writing in London in 1663. The first enthusiasts were therefore the English, and it was only afterwards that it became fashionable in France, especially in Paris.

In the last third of the 17th century, it became common practice in Champagne to add sugar and molasses to the wine during bottling in order to obtain sparkling and effervescent wines. The sparkling product was then deliberately produced in larger quantities towards the end of the century. However, even thick-walled bottles were very often unable to withstand the high carbon dioxide pressure caused by the copious addition of sugar and vigorous fermentation. Around 80% of all bottles were broken at the time. As a result, only a few thousand bottles were produced each year throughout the 18th century. And these were extremely expensive. For this reason, champagne initially developed exclusively as a fashionable drink in aristocratic circles or among the wealthy.

Large-scale production of champagne only began in the first third of the 19th century, when the problem of the correct sugar dosage was solved. The chemist Jean-Antoine Claude Chaptal (1756-1832) helped to clarify the issue. He recognised that the cause of foaming in the bottle was unfinished fermentation. However, the greatest achievement was made by the pharmacist Jean-Baptiste François (1792-1838), who discovered the secret of the correct amount of sugar. Other milestones were the improvement of corks, the corking machine and, at the Veuve Clicquot-Ponsardin Champagne House, the invention of the vibrating console for remuage by the legendary cellar master Antoine de Muller (1788-1859).

Region of origin

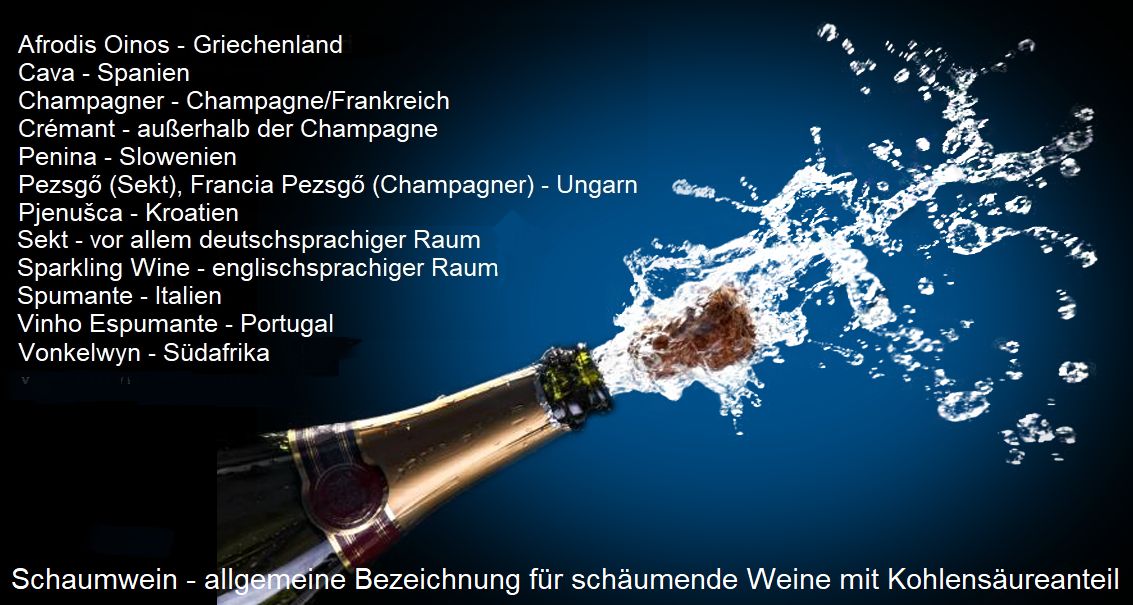

Champagne and the Champagne produced here enjoy the status of an Appellation d'Origine Protégée (AOP), even if this is not usually stated on the label. It is predominantly produced in white and in smaller quantities also as rosé, but there is no red as in the case of sparkling wine. According to the strict conditions of the CIVC, sparkling wine may only be called Champagne or Champagne) if it fulfils precisely regulated specifications regarding its origin. The grapes must be grown and pressed in the "Région délimitée de la Champagne viticole" and fermented in double fermentation according to the Méthode champenoise, which was established in 1935. This was laid down by an EU regulation in 1994 after endless legal disputes. Outside Champagne (and also in other countries), a quality sparkling wine is known as Crémant and in German-speaking countries as Sekt. The country-specific designations are:

The name Champagne is not only protected within the European Union, but in a total of 120 countries worldwide. In Russia, however, a law was passed in 2021 that the name "Champagne" may only be used for Russian sparkling wines. According to the new law, French champagnes must be labelled with the addition "sparkling wine". The word Champagne may only appear on the label in Latin and not in Cyrillic script. "Champagne" is now written in small letters on the back of the label.

Grape varieties

Seven varieties are authorised, of which only Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier and Chardonnay play a role. The four varieties Arbane, Petit Meslier, Fromenteau (Pinot Gris ) and Pinot Blanc are authorised for historical reasons, but only occupy 90 hectares. Authorised training forms are Chablis, Cordon de Royat, Guyot and Vallée de la Marne. These are short prunings that guarantee moderate production. The maximum yield is set annually by the CIVC and depends on the weather and the economic situation. If there is an oversupply of Champagne, production is reduced. In 2019, this was 10,200 kg/ha of grapes (2018: 10,800 kg/ha).

Production of champagne

Champagne production is an extremely complex and complicated process. The chronicler Henry Vizetelly (1820-1894) described this in his book "A History of Champagne", published in 1882: Good champagne does not fall from the sky, nor does it leap from the rocks; rather, it is the result of tireless labour, prudent expertise, the most precise care and the most careful observation. The special thing about champagne is that its production only begins where the production of other wines usually ends. Champagne is the subject of countless legends and anecdotes. Madame Pompadour (1721-1764), mistress of King Louis XV (1710-1774), said: "Champagne is the only drink that makes women more beautiful the more they drink of it. Incidentally, her favourite brand came from the house of Moët et Chandon. However, the most beautiful anecdote is undoubtedly that of the legendary Madame Lily Bollinger (1899-1977).

The individual steps listed below essentially correspond to the production of a bottle-fermented sparkling wine (quality sparkling wine) or sparkling wine.

Grape harvest

As a rule, the grapes are harvested early. This means that they have not yet reached full ripeness and have a lower must weight. A low yield does not play a major role either. The main criterion for the optimal quality of the grapes is not a high sugar content, but the ability to produce acid-emphasised base wines. Furthermore, astringent phenols (tannins) are undesirable. The grapes are harvested by hand and all unripe and rotten grapes are removed. The minimum quantity for the potential alcohol content in the must is set annually (around 9% vol.). The grape prices are determined annually according to market-specific criteria, whereby the Échelle des crus system with the classification into Grand Cru, Premiere Cru and other communes serves as a guide.

Pressing

The maximum yield is limited to 102 litres of must (produces 100 litres of wine) from 160 kg of grapes. Only gentle whole-cluster pressing is permitted. The traditional presses hold 4,000 kg (1 marc) of grapes, from which 2,550 litres of must may be extracted. The quantities result from the 205 litre Pièce champenoise barrel type used here. The 2,050 litres (10 pièces) resulting from the first pressing are called tête de cuvée, which is the best quality. This is followed by a "taillieren" (turning over) of the mash and a further pressing process. The remaining 500 litres are called taille (until 1990 there were two pièces premième taille of 410 litres and one pièce deuxième taille of 205 litres). Only these musts may be used for champagne. The must from other pressing operations is called "Rebéche" and is only authorised for distillation.

Fermentation of the base wine

The quality of the base wine plays an important role in the final product. For high-quality sparkling wines, the quality of the base wines (see details there) must also be excellent. However, different requirements apply than for ordinary still wines. Many champagne houses only use the best must (Tête de Cuvée) for the production of the base wines. The must is clarified at a low temperature for 12 to 48 hours by settling before fermentation (débourbage). It is then transferred to the fermentation tanks, whereby most companies use steel tanks with a volume of 50 to 1,200 hectolitres, although a few still use traditional oak barrels. Yeasts recommended by the CIVC are often used. The fermentation temperature is between 12 and 25 °Celsius. At around 22 °Celsius, alcoholic fermentation takes around three weeks. Most wines then undergo malolactic fermentation. This is followed by further clarification and the end product is called "vin clair". The base wines usually have an inconspicuous, acidic flavour compared to still wines.

Assemblage (blending)

This process determines the distinctiveness and quality of the product. The selection and blending of wines and vintages requires experience, sensory skills, imagination and care. The details are a closely guarded secret of the champagne houses. At this point, it is decided whether the wine quality is sufficient to create a Millésime (vintage champagne), which is only done in particularly good years (at the discretion of the houses). According to EU regulations, such a champagne must contain at least 85% of the specified vintage, but this has been tightened to 100% by the CIVC. In the case of non-vintage champagnes, the blend is made from different vintages or wines. At Moët et Chandon, a cuvée of up to 30 batches is composed from the huge reservoir of 300 base wines. This can also include the reserve wine. The "Grande Cuvée" from the Krug champagne house even consists of up to 60 different wines. The wine may not be drawn off into bottles for the subsequent bottle fermentation before 1 January of the year following the grape harvest.

Liqueur de tirage and bottle fermentation

A fundamental rule is that Champagne must undergo a second fermentation in the bottle (not in a tank or barrel) after the alcoholic fermentation. Until 2001, the fact that champagne must be fermented in the bottle in which it is marketed was restricted to the standard bottle (0.75 litre) and magnum (1.5 litre) formats. All small and remaining large formats could be filled from standard bottles. Since the beginning of 2002, half-bottles (0.375 litres) and Jeroboams (3 litres) must now also be originally bottle-fermented. Some producers such as Krug or Pommery have always treated all their formats in this way.

Liqueur de tirage is added to the base wine to trigger bottle fermentation . Depending on the residual sugar, this is a small amount of a mixture of cane sugar dissolved in wine and special yeasts of around 25 g/litre. Many producers add riddling aids such as bentonite to facilitate the subsequent disgorgement (removal of the yeast sediment). The wine is then bottled and sealed with a crown cap. Some producers attach a small, thimble-sized plastic cup (bidule) to the inside of the crown cork to hold the yeast sediment.

Bottle fermentation takes around ten days to three months or longer at relatively low temperatures between 9 and 12 °Celsius. The alcohol content increases by around 1.2% to 1.3% vol. Under high pressure of at least 3.5 to 6 bar, the typical, extremely fine-pearled foam (French "prise de mousse") is created in the form of carbon dioxide. The champagne's (sparkling wine's) high effervescence with tiny bubbles is a decisive quality criterion.

Sur lie (lees ageing)

Bottle fermentation produces a sediment of dead yeast cells (lie) and other turbid matter, which plays an important role in the ageing process. The bottles must now be stored for at least 15 months (including at least 12 months on the lees), or three years in the case of vintage champagne. But there are also champagnes with 10, 20 and sometimes even up to 50 years of ageing. The longer the ageing on the lees, the shorter the drinkability when opened. On average, however, the storage time for non-vintage products is 2.5 to 5 years. During this time, substances are absorbed from the dead yeast residue and the fine, typical flavour develops.

Remuage (riddling)

The bottles are placed upside down in the pupitres (riddling desks), which are initially set at a very steep angle. For up to three months, they are manually shaken by the remuageur (riddling master) every day, turned around an eighth of a circle and the lectern placed slightly flatter until the bottles are upside down and the sediment in the bottle neck is behind the cork. This is usually done 24 to 32 times. As a positioning aid for the remuageur, many houses attach a cellar point (marque) to the bottom of the bottle. Experienced remuageurs can handle 30,000 to 50,000 bottles of champagne per day. The time-consuming and labour-intensive manual remuage is now carried out by large companies using gyropalettes (computer-controlled metal crates), which shortens the process to one week. The latest processes are intended to make both remuage and gyropalettes superfluous. Highly adsorptive alginates are used for this purpose.

disgorgement (remove yeast sediment)

Certain houses delay the removal of the lees for as long as possible after remuage in order to increase the fullness of flavour through long storage on the lees. A protected trademark of the Bollinger Champagne House in this respect is Récemment dégorgé (RD). Hot disgorging (disgorgement à la volée) requires great skill to avoid excessive losses. Today, cold disgorging (disgorgement à la glace) is predominantly used. The bottles are placed with their necks in an ice-cold salt solution and then opened (disgorging hook). The almost frozen lump of yeast shoots out; the champagne splashed in the process is topped up if necessary. The video (click to view) shows the manual process at the Philipponnat Champagne House; the yeast sediment can be seen in the neck of the bottle:

Liqueur d'expédition, corking and poignettage

Alternatively, the so-called liqueur d'expédition (shipping dosage) is now added to the bottles. This is a mixture of wine and cane sugar or, for some producers, brandy. This replaces the quantity missing in the bottle due to the removal of the yeast and gives the champagne the desired degree of sweetness (sugar content). Some producers do not use this dosage for high-quality vintage champagne or champagne that has been stored on the lees for a very long time. In this case, the label will say pas dosé, dosage zéro or Brut nature (meaning "without dosage"). After the cork has been driven into the neck of the bottle by compression, it is covered with a metal cap (capsule), which in turn is held in place by a wire basket (muselet) known as an agraffe. In order to optimally combine the dosage with the wine, the bottles may be shaken manually or mechanically, also known as piquetage. The video clip (click to view) shows the mechanical addition of the shipping dosage and corking at the Billiot company.

Quality control

Champagne is one of the most strictly controlled products in the world. A total of five institutions check the specifications and quality. These are the Ministry of Agriculture, the State Wine Control and Trade Inspectorate, the INAO, the customs and tax authorities and the Champagne Association CIVC (Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne). The name "Champagne" must appear on the label and, in the case of vintage Champagne, the year. Both must also be branded into the cork. Each Champagne label bears a six- to seven-digit control number assigned by the CIVC. The first one or two digits indicate the type of producer or bottler:

- CM = Coopérative de Manipulation (trade mark of a co-operative)

- MA = Marque d'Acheteur (special trade mark - produced for supermarkets, restaurants)

- ND = Négociant Distributeur (buys, labels and distributes champagne)

- NM = Négociant Manipulant (buys grapes, must, base wine - processes, distributes)

- R = Récoltant (independent winemaker, has champagne produced on a contract basis)

- RC = Récoltant Coopérateur (G member, supplies grapes and receives champagne)

- RM = Récoltant Manipulant (produces champagne from his own grapes)

- SR = Société de Récoltants (related producers' association)

Bottle sizes

Special oversized bottles are often used for Champagne (sparkling wines), which are often named after famous biblical figures. As production is very cost-intensive and time-consuming, not all champagne houses do this and only in small quantities (see Bottles).

Producers

There are around 15,000 Champagne winegrowers, many of whom are small, grape-only producers with just a few hectares of vines. But around 5,000 of them, as well as 60 co-operatives and 360 trading houses, produce Champagne. These produce at least one, some even hundreds of brands (in this case mainly MAs). The small producers, often with only a few thousand bottles, very often produce amazing qualities because, unlike the large houses, they can use all the grapes from Grand Cru plots. A total of 11,000 champagne brands are registered with the CIVC.

A total of around 300 million bottles are marketed each year. This means that, on average, ten bottles are opened every second worldwide. Around 40% of the total volume is exported. The main customers are the UK, USA and Germany. The programme of large companies includes a vintage-free standard quality, a vintage champagne, a blanc de blancs (chardonnay), a rosé and a cuvée de prestige as the top product of the house. Some companies also produce non-sparkling red, rosé and white wines under the AOC Coteaux Champenois.

Well-known producers and brands Well-known producers and brands include Ayala, Besserat de Bellefon, Billecart-Salmon, Billiot, Binet, Bollinger, Canard-Duchêne, Charles Heidsieck, Delamotte, Deutz, Drappier, Duval-Leroy, Fleury Père et Fils, Gosset, Alfred Gratien, Heidsieck Monopole, Henriot, Krug, Jacquart, Jacquesson, Joseph Perrier, Laherte Frères, Lanson, Larmandier-Bernier, Laurent-Perrier, Mercier, Moët et Chandon, Mumm, Nicolas Feuillatte (Palmes d'Or), Perrier-Jouët, Philipponnat, Piollot, Piper Heidsieck, Paillard, Pol Roger, Pommery, Roederer, Ruinart, Salon, Taittinger, Tarlant, Thiénot, Union Champagne, Veuve Clicquot-Ponsardin and Vranken.

Sponsorship of Formula 1 races

At car races, it has long been customary to present a bottle of champagne to the winner, who shakes it and then sprays it on the runner-up and third-placed drivers, as well as into the crowd. In the long history of Formula 1, these were brands from various producers such as Moët et Chandon, Domaine Chandon and Mumm. Initially, magnum bottles (1.5 litres = 2 normal bottles of 0.75 litres each) and then jeroboam bottles (3 litres = 4 normal bottles) were used.

Champagne enjoyment

A question that is often asked is whether champagne is suitable for long storage and develops in the same way as a high-quality still wine. As a rule, it has already reached its peak from the time of commercialisation (see under sparkling wine). Several discoveries of bottles in shipwrecks have shown that the "ideal storage conditions" (dark, cool, high pressure, quiet storage) mean that even very old champagnes can still be enjoyed. The record is held by a Veuve Clicquot from the 1839 vintage found in a wreck in 2010, which was not only drinkable after more than 170 years, but even tasted excellent. A diverse culture has developed around the enjoyment of champagne (sparkling wine). For example, it is a tradition and international standard to use champagne for ship christenings.

Further information

For more information on this topic, see also champagne cocktail, champagne bottle, champagne glass, champagne bucket, Champagne tower, champagne stopper, champagne tongs, placomusophilia and sabering (champagne heads).

With regard to the legal wine specifications from dry to sweet for still wines and sparkling wines, see under sugar content.

For the production of alcoholic beverages, see also Distillation (distillates), Spirits (types), Winemaking (wines and wine types) and Wine law (wine law issues).

Source

An informative website about champagne is www.champagne.com. With the kind permission of the author John McCabe, this work has been used as a source for descriptions of the operations of many of the Champagne houses listed.

Dom Perignon: By Victor Grigas - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

Rüttelpult: By Manikom - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

Remuage: Champagne house Schlumberger

disgorgementChampagne house Philipponnat

Bottle sizes: © Norbert F. J. Tischelmayer

Classified wine producers in Champagne 67

find+buy for Champagne 91

Recent wines 454

Laurent-Perrier

— Champagne

Champagne AOC Brut Nature "Blanc de Blancs"

Laurent-Perrier

— Champagne

Champagne AOC Brut Nature "Blanc de Blancs"

Champagne Laurent Lequart

— Champagne

Champagne AOC Pinot Meunier Réserve Extra Brut

87 WP

very good

27.60 €

Champagne Laurent Lequart

— Champagne

Champagne AOC Pinot Meunier Réserve Extra Brut

87 WP

very good

27.60 €

Champagne Laurent Lequart

— Champagne

Champagne AOC Extra Brut Cuvée "Prestige"

90 WP

excellent

54.80 €

Champagne Laurent Lequart

— Champagne

Champagne AOC Extra Brut Cuvée "Prestige"

90 WP

excellent

54.80 €

The most important grape varieties

More information in the magazine

- Pinot Meunier awakens from a deep sleep Champagne: renaissance of an underrated variety

- Record sales and slavery in Champagne Streaming tip: Exploited for champagne

- Paradisiacal times! Tasting: European sparkling wines for the festive season

- Lots of freshness after 40 years of bottle ageing Piper Heidsieck winemaker Emilien Boutillat launches collector's series for fans

- Biodiversity instead of monoculture in the Champagne vineyards Ruinart plants around 20,000 trees and bushes with the "Vitiforestry" project

- Back to the cork, forward to sustainability How the Ruinart champagne house is adapting its production to climate change

- The right twist In the test: Sparkling wine opener

- How the Viennese Waltz became world famous with champagne Ron Merlino on Johann Strauss and the good business of wine and music

- Plaimont - The vine rescuers from south-west France Advertisement

- Good Bordeaux doesn't have to be expensive! Crus Bourgeois